In its most fundamental sense, the term “avoidance” refers to behaviors that are carried out in an effort to prevent or avoid danger. Avoidance learning is the process of learning to employ avoidance behaviors in certain circumstances.

What is Avoidance Learning?

An easy way of understanding avoidance responses is by comparison to escape responses. An escape response is carried out in an attempt to escape once an aversive (unpleasant) stimulus is presented – for example, attempting to cover one’s ears when confronted with an uncomfortably loud noise. On the other hand, an avoidance response is a learned, voluntary behavior which is carried out to prevent or avoid an aversive stimulus before it is presented: for example, putting earplugs in before entering an environment where loud noises might occur.

Such an avoidance response can only take place after avoidance learning has occurred, where a subject learns to associate the unpleasant unconditioned stimulus (e.g., a loud noise) with a conditioned stimulus (e.g., entering a certain environment).

Avoidance learning can be further categorized. Passive avoidance, for example, refers to avoidance behaviors where a subject withholds certain behaviors to avoid an aversive stimulus. Active avoidance, where a subject takes action to avoid harm, may be carried out in response to a warning signal (signaled active avoidance) or not (unsignaled avoidance).

In practice, the term “avoidance” is also used to refer to the behavioral conditioning techniques used in laboratories to instill avoidance learning in subjects, and to a type of coping strategy employed by anxious people.1,2

Avoidance learning and avoidance behaviors can be considered natural and essential parts of avoiding danger and preventing harm. However, excessive or unnecessary avoidance behaviors are considered to be a hallmark of anxiety disorders.3 Because of this, research into avoidance learning is a common avenue of inquiry in experimental psychology, and one that is typically investigated using rat or mouse models in the lab.

The Origins and Evolution Of Avoidance Learning Research

In the late 1930s, researchers began investigating avoidance learning in order to gain insight into fear and anxiety.4 Active avoidance learning was initially considered to be a two-factor learning process consisting of fear conditioning, followed by instrumental conditioning.

In fear conditioning, a subject acquires fear of a certain unconditioned stimulus (e.g., an electric shock) through Pavlovian conditioning. The following instrumental conditioning (or operant conditioning) phase involves reinforcing an association between the unconditioned stimulus and a harmless conditioned stimulus such as a light or sound.

Over time, criticisms of this conceptualization of avoidance learning arose – in particular, psychologists disagreed over whether fear reduction could reduce avoidance, and whether avoidance responses could really be considered instrumental in nature. By the mid-1980s, this led to experimental avoidance learning models falling out of favor as a route to understanding fear and anxiety.5

However, recent advancements in understanding the neural basis of Pavlovian conditioning have precipitated a new wave of interest in experimental avoidance learning research. This work has provided new insights into avoidance learning as a product of Pavlovian and instrumental learning and habit learning; conceptualizing reinforcement in terms of molecular and cellular events in specific neural circuits.

The GEMINI System: Optimized for Avoidance Learning Research

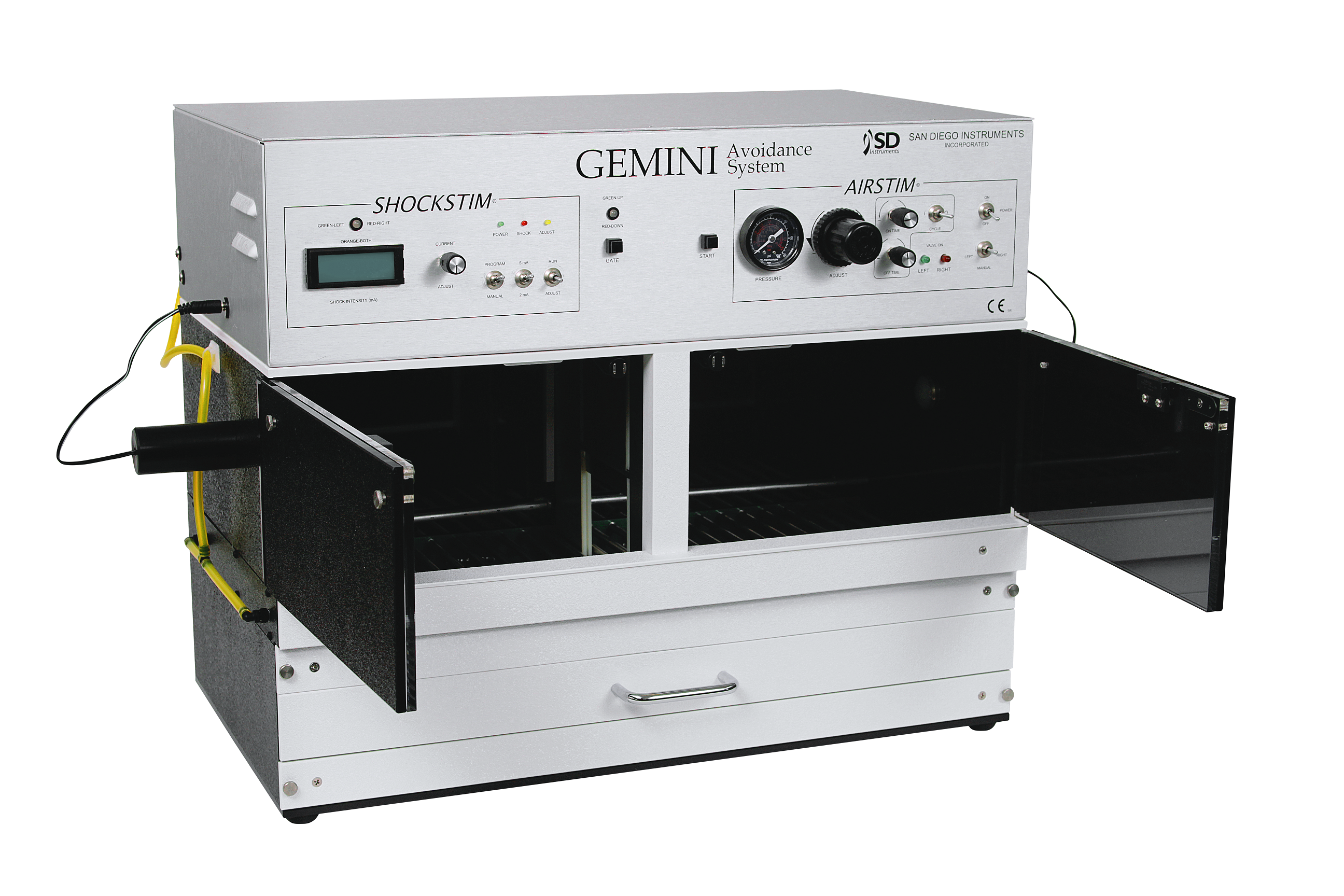

San Diego Instruments developed the GEMINI active and passive avoidance system to provide a versatile self-contained solution for avoidance learning studies using rats and mice.

Unlike other systems, GEMINI’s hardware and software were both developed for the sole purpose of avoidance learning tests. Up to 8 independent avoidance learning chambers can be configured for rapid testing of subjects using either shock or air puff as unconditioned stimuli. Built-in cues – which can be used individually or in combination – include non-heating LED house lights, laboratory standard cue lights, user-configurable auditory stimuli, and a quiet auto door.

With the GEMINI system, entire studies can be defined in advance in accordance with different avoidance testing protocol definitions to test active avoidance, passive avoidance, and learned helplessness behavior. Our proprietary software makes it easy to plan session parameters and ensures that results are tightly coupled to predefined subject identifiers.

To find out more about the GEMINI active and passive avoidance system, read the full product description here or get in touch with a member of the San Diego Instruments team today.

- Sidman, M. Avoidance Conditioning with Brief Shock and No Exteroceptive Warning Signal. Science (1953).

- Weinbrecht, A., Schulze, L., Boettcher, J. & Renneberg, B. Avoidant Personality Disorder: a Current Review. Curr Psychiatry Rep 18, 29 (2016).

- Holahan, C. J. & Moos, R. H. Risk, resistance, and psychological distress: A longitudinal analysis with adults and children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 96, 3–13 (1987).

- Mowrer, O. H. A stimulus-response analysis of anxiety and its role as a reinforcing agent. Psychological Review 46, 553–565 (1939).

- LeDoux, J. E., Moscarello, J., Sears, R. & Campese, V. The birth, death and resurrection of avoidance: a reconceptualization of a troubled paradigm. Mol Psychiatry 22, 24–36 (2017).